■ Features

In March 2020, the music industry came to a standstill. By September 2020 Installation International estimated over a million people in the live events sector had lost their jobs and many independent venues faced permanent closure due to rent prices and inadequate government support. The future looked bleak. However, there was one part of the industry that researchers thought may survive this pandemic unscathed: music streaming services.

The UK firm PWC commented on streaming during the pandemic suggesting that although music fans cannot attend live music events, listening to music via various streaming services will be their first point of call:

“As people turn to music for emotional support and comfort in these tough times, any negative impact on music listening has been more limited”.

According to Times International, artists in 2020 earn around “$0.006 to $0.0084” for each individual stream of their song. If an artist received 1000 streams on a song they would be paid roughly $4.37. These numbers clearly show that even if small artists were able to have their music streamed more, they would not make anywhere near the same amount of money that they would from even one live show.

Nevertheless, PWC believes that the rise of streaming is the right direction for music consumption to be headed. They explain:

“In our view, COVID-19 will impact some revenue streams [...] The continued trend to on-demand should continue which will help to support the valuation of music rights assets.”

For a tiny percentage of hugely popular artists an increase in streaming may positively impact their income during a pandemic if streaming numbers were to increase. However, for the majority of live performers, revenue generated from streaming will remain negligible not only for the length of a pandemic, but for the length of their careers.

On top of this, when PWC released the findings from their research, streaming numbers hadn’t increased. In fact, they had dramatically lowered:

“The New York Times reported on 6 April that the combined streams of the top 200 on Spotify in the US slipped for the third consecutive week - hitting the lowest point of the year”.

With streaming numbers experiencing a significant drop, we can only assume that virtually no artist in the world has come out of the pandemic financially unscathed.

So, how did we stop buying music and is there a way back? In an article from 2019 discussing how the music industry has changed in the last decade, Elana Rubin lists a few reasons for the rise of streaming.

A higher level of technology developed over the past decade has a big part to play. Ten years ago it was more common to listen to music on an iPod loaded with music bought from iTunes than to stream music over WiFi on mobile devices.

Rubin also mentions the decline of physical music sales over the years. According to a report by the Recording Industry of America, streaming makes up around 80% of revenue for the US music industry, whereas physical music sales make up around 9%. The fact that there are any significant physical music sales at all could be attributed to the rise of vinyl collecting. Despite the decline in buying music, vinyl sales have increased by 15% between the years of 2018 and 2019.

Whilst getting paid for your music appears to have largely gone out the window in today’s industry, the likes of music blog Burstimo are quick to point out the benefits of such technological advances for artists - namely the potential for greater and cheaper exposure.

Burstimo points out that an artist can post a song on social media, and have a potential reach of just under half of the world’s population. 15 years ago an artist would have to work harder to have people listen to their music; whether this be by giving their music out for free, or posting CD’s to radio stations. This would cost an artist a large amount of money and time.

Burstimo suggests that everyone is now able to put their music online at a low cost, make money from it, and ‘get noticed’. In the age of social media, it can be argued that anyone can put content on social media and create revenue.

Rubin also gets at this idea when she discusses the ‘surprise drop’. In 2013, when Beyoncé released her self-titled album without any marketing leading up to it, the singer sold 5 million units of the album, earning a Guinness World Record.

To look into this topic further, I created a questionnaire, prompting participants to share their experience of working in the music industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was found that a large number of participants had been furloughed, stopped working, or become unemployed. Participants responded that they had “lost income”, and “had to put things on hold”. 34.7% of those surveyed responded that they could not work during the pandemic at all.

When asked about any positive outcomes of the pandemic, greater connectivity online was something that was widely expressed. Some found that online networking was a way to keep themselves present in the minds of professionals. Others found that building their social media presence was a great way to occupy their time. However, no one reported any financial gain from such activity.

When asked what their concerns were for the future of the music industry, many expressed their frustration that “streaming services do not pay artists appropriately”.

The decline of buying music isn’t a new phenomenon. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has emphasised the extent to which this revenue stream for musicians has been obliterated. In times such as these, with the industry on its knees, it’s important to support the musicians you care about and buy their music and merchandise if at all possible.

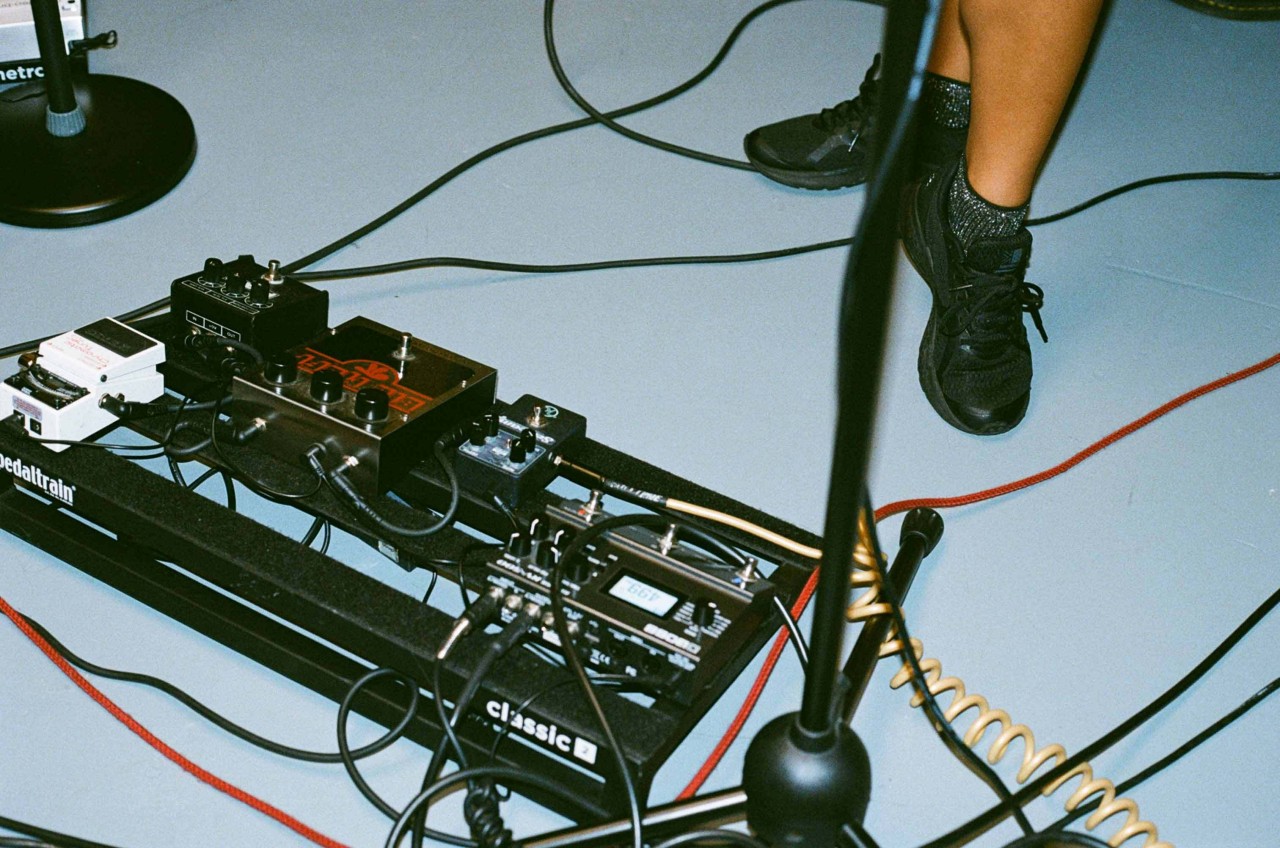

Amelia Jones (inkblots) is a photographer, filmmaker and motion graphics editor from the North West of England. She specialises in portraits, gig and concert photography and videography.

You can keep up with Amelia by following her on Instagram.

You can keep up with Amelia by following her on Instagram.