■ Features

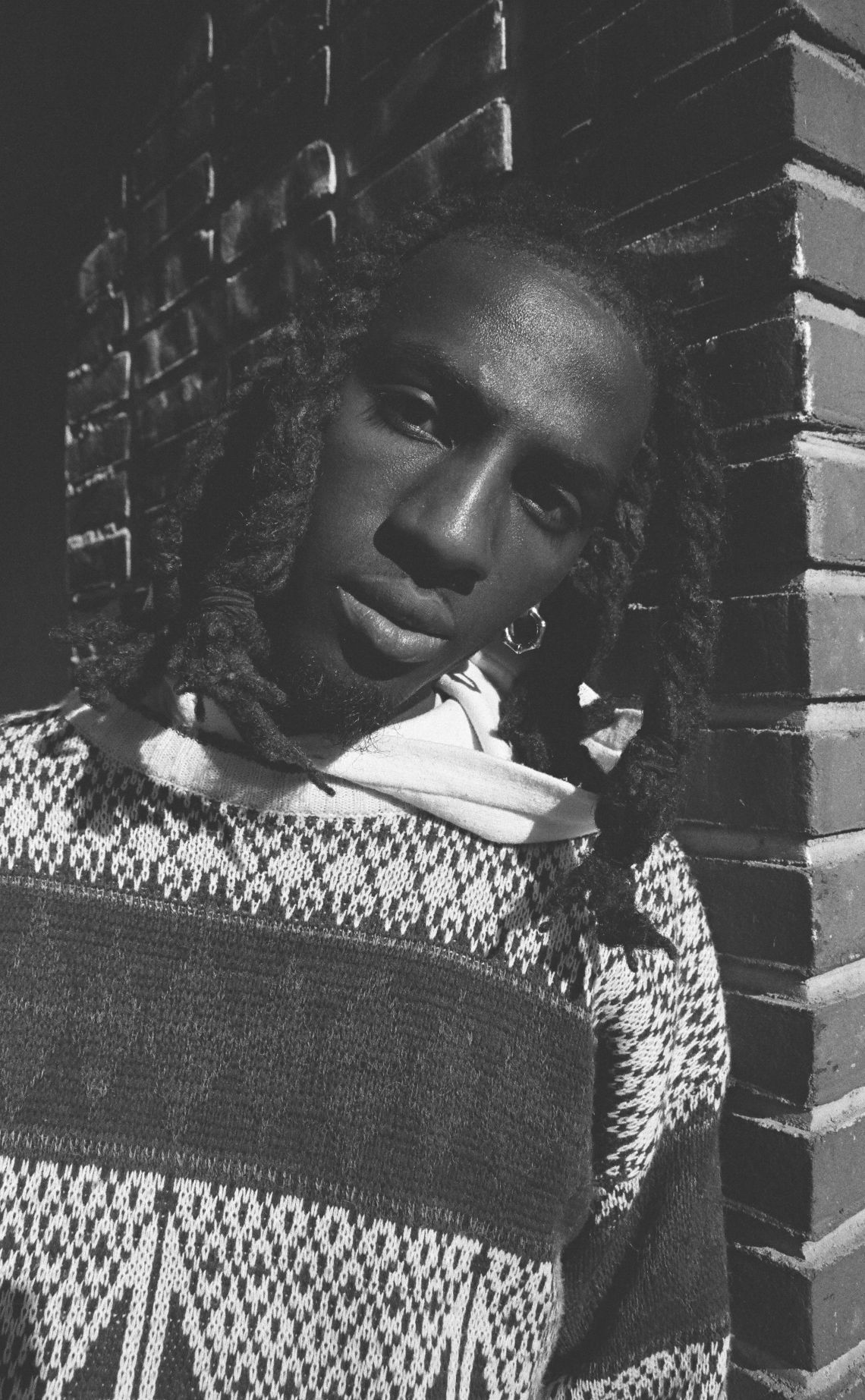

Rapper Wakai reportedly hasn’t spent over a month in the same city this year, just how he likes it.

Arielle Lana LeJarde digs into why the Louisiana lyricist loves life on the road so much.

When people think of Baton Rouge, oftentimes the first thing that comes to mind is how the city continues to top national lists of high crime per capita, year after year. Even the first three queries on Google are related to how safe the city is.

Louisiana State University sociology professor, Ed Shihadeh, and East Baton Rouge Parish District Attorney, Hillar Moore both attribute this to its lack of resources, Moore explains:

“Look at every other list that Louisiana and Baton Rouge [are on] — literacy, poverty, all of those things, Louisiana’s either at the top or the bottom of where you don’t want to be.”

While the city’s reputation might not be unfounded, its chronicled context of marginalization also can’t be ignored.

Its French ancestry dates back to 1698, when Pierre Le Moyne D’Iberville led French colonizers onto the land. By 1846, the United States had acquired the state and Baton Rouge was solidified as its capital to supersede the “sinful” New Orleans. And ever since the American Civil War, the city has had a recorded past of voter suppression and intimidation of Black Americans, leading to the historical disenfranchisement of its populace.

Baton Rouge resident and rising rapper Wakai, however, presents a perspective rooted in respect and love for his hometown. “It’s great,” he shares, describing a unique spirit:

“People who don’t know you will help you bring your groceries to your car. People will literally wait for you to hold the door for you. It’s just hospitality, like, everywhere.”

But the last time I spoke to Wakai, he shared that the reason he explores new cities so often is that people operate on a seemingly “lower frequency” in Baton Rouge, he goes on to say:

“The same person that holds the door for you will be the person that scams you. That’s just how it is. That’s the culture.”

And like Shihadeh and Moore, Wakai credits the lack of community resources, expressive outlets, and good role models to the culture that’s been cultivated.

Luckily for the artist, Wakai was blessed with plenty of sources of inspiration to look up to, and they helped direct him onto his current path.

“I had a bunch of great role models,” he smiles. “My aunts, my uncles, my cousins, my sisters.” Despite not having the best high school experience himself, he was friends with people all over his city, noting that he was the type of guy to be invited to every school prom.

And his high school experience might make for the perfect metaphor for how he currently lives his life.

While Wakai might feel stuck in an environment that’s not conducive to his mental, spiritual, or professional growth, he always manages to find a way to make the most out of it.

His ability to connect with people has also granted him a plethora of opportunities to travel. As a matter of fact, as we sat in one of Pirate’s Bushwick recording studios, he was visiting New York for a performance in Manhattan the next day.

In the recently released 'To a Dark Boy' documentary, Wakai’s co-manager Nye Moody shares:

“I don’t think that Wakai’s spent more than a month in the same city for the past year.”

Asked about this, the rapper tells us:

“Even early in [the] Soundcloud [days], I was cool with people in London, I was cool with people in Cali, I was cool with a lot of different people. I just couldn’t travel yet. It was small little baby steps, but I was planting seeds. I wanted to befriend someone here [and there] so that eventually I can have a bond with someone everywhere.”

But that’s not to say Wakai isn’t genuine in the way he moves. His appreciation for authentic collaboration and connection is rare to find in the music industry, especially when one sees rampant growth as Wakai has in the past year.

“When Tupac got out of jail… That’s the mentality I’ve had since I was 12,” he articulates, elaborating:

“When there’s nothing left I can do in this physical realm, the people I’ve impacted and touched will say that I’ve worked towards the betterment of myself and the betterment of what I was passionate about. And what I’m passionate about is my art.”

But for Wakai, traveling isn’t just an escape from the blights of Baton Rouge, it also allows him to experience growth and see from new perspectives.

His latest album, 'To a Dark Boy,' was recorded all over the country. His track '1102' was created in Pirate’s Gowanus studios in Brooklyn, 'When There Was No Sun' in the Silver Lake studios in L.A., and 'Lively' on his friend’s couch in Seattle.

Especially after being in lockdown, finally meeting people face-to-face added humanity back into collaboration, permitting sincere links to form with producers, vocalists, rappers, and other artists from around the world.

Wakai’s compassionately warm and whimsical nature is probably why he’s able to jell in so many different circles.

And his passion for both voyage and helping people is ancestral. He stops our conversation to point to the tattoo of Africa on his forearm, saying:

“This is a slave map with a compass that told people where to go and how to get out.”

The Louisiana lyricist acknowledges even now, most people from his community don’t have the luxury of packing up and going wherever they want, whenever they want. So in a way, his journey and successes are a vehicle for people to live vicariously through him.

“I go on my [Instagram] story and I don’t care how headass it looks,” he laughs before describing the significance of what he's really doing:

“They don’t see things like that back home. Even the little bridge by the studio or a woman in the train station selling churros. Certain things might not mean anything to a person who lives here, but they mean the most to me because I’m able to show people who never get to see them.”

Arielle Lana LeJarde is a Brooklyn-based culture writer and music journalist who has written for Pitchfork, Mixmag, MTV News, and more. Follow her on Twitter.

Wakai is photographed by Peter Suski in Bushwick, NYC.