■ Features

Will Bradbury explains how to find samples from songs to use in your own music production, legally.

Simply put, a sample is a section of audio derived from another source, which is then reused in the creation of a new track.

A sample can be anything from a short drum hit (e.g. a single kick or hi-hat sound) to a full drum kit breakbeat to a soul acapella or even longer recordings like a field sample.

These are often manipulated through various processes — repitched, sped up or slowed down, layered or looped — which often leaves the sample indistinguishable from its original sound.

In recent years, sampling has become an incredibly important aspect of music production, providing the foundation to almost all hip hop, electronic and pop music where drum sampling tends to form the backbone for most tracks.

Albums can even be made in their entirety (or almost) using samples.

DJ Shadow was the first to do this with his iconic 1996 album Endtroducing….., The Avalanches' track Since I Left You, released at the turn of the millennium sounds almost like a statement on the endless possibilities sampling provides — plundering influences spanning a myriad of genres into a giant sampled melting pot which sounds like nothing else before or since.

For more on how sampling transformed music, you may want to check out Mark Ronson’s Ted Talk.

Given how easy it is to repurpose music in this fashion has given rise to increasing questions on the ownership of audio recordings. By and large, you should not be worried about the use of other samples in the writing process. Short samples and break beats are never going to be an issue.

If you’re using a really recognisable sample as a centrepiece of a track you’re making, get it finished first. You never know, you may write an absolute banger. If that’s the case, you’ll need to look at getting it cleared from the copyright owner, something we will explore later.

Arguably the first use of sampling came about in the 40s and the birth of music concréte, when composers began using tape loops as part of their performances. That same decade, the first sample-based electro-mechanical instrument was created, The Chamberlin, which was essentially a keyboard which triggered a tape-playing mechanism when each key was pressed.

But the term ‘sample’ was coined much later by Kim Ryrie and Peter Vogel in reference to the Fairlight CMI.

Their interest in computers led to them developing this synthesizer, which is one of the earliest music workstations with an embedded sampler, capable of capturing short recordings for playback on a keyboard. Not only was it widely used by some of the biggest stars of that generation from Kate Bush to Herbie Hancock, but precipitated the invention of further sample-based synths, such as the legendary Korg M1, which came with in-built effects such as reverb, delay, chorus and more.

Then in the late 80s, the famed engineer and designer of electronic instruments Roger Linn birthed the first integrated drum sampler and midi sequencer in collaboration with the Japanese company Akai.

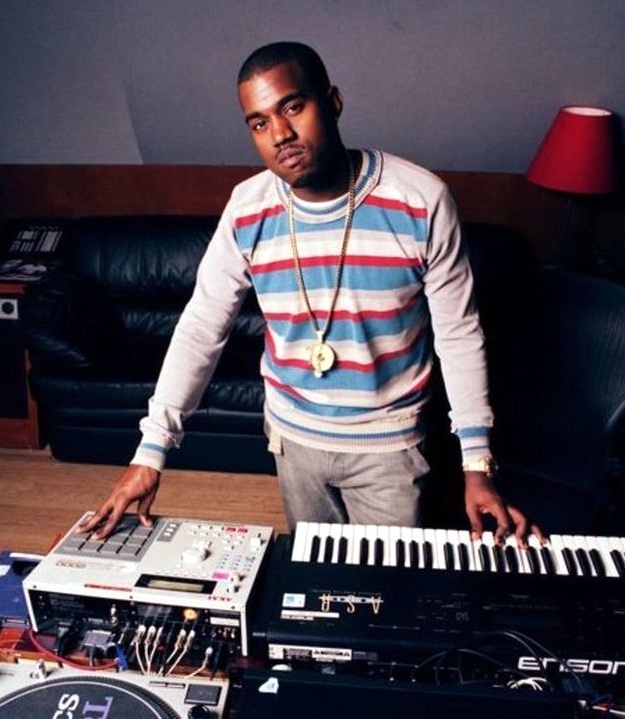

Its first inauguration, the MPC60, was a groundbreaking innovation, particularly in the world of hip hop and dance music, allowing users to assign samples to pads and trigger them independently, as if playing a keyboard or drum kit. If you’ve seen the recent jeen-yus film you may have caught Kanye laying down a beat on one of these in an early makeshift studio.

These days, with the affordability and ubiquity of computers, most people use samplers inbuilt into their digital audio workstations (DAWs), be that Ableton, Logic or Protools.

Most people prefer the speed, ease and control of software, though some, particularly those who began working on outboard instruments may still opt for this method to provide a more ‘human’ feeling to their workflow.

Another reason people may want to look at buying an MPC/standalone sampler is for performing live.

If sampling live is something you want to explore, do you research, and even go into a hardware store to test out a few models — the market is flush with them!

Each MPC will have their unique properties, sequencing capabilities, fx, look and feel. Some prefer a slick modern option such as the Elektron Octatrack whereas others may prefer a more old-school machine such as the MPC One Retro, which is inspired by their early models — MPC 2000, MPC 3000 and the MPC 60. Alternatively, you could look at buying a midi controller to trigger samples from your laptop live on stage.

Whether or not you’re looking to load them into a sampler or simply work in a DAW when you’re writing a track, you’ll need to get them from somewhere.

So, where do producers get samples? Here are five places to look:

TIP! It’s a good idea to bounce the shorter snippet of audio you want to use into another file — a technique called re-sampling. This is also particularly useful if you have heavily processed something, as it will save your CPU usage, meaning your computer won’t have to work so hard and potentially bug out.

As mentioned previously, warping samples into something unique will not only save you the trouble of having to clear samples, but can produce bonkers results.

I’ll quickly run through a few ways you can experiment with your samples but as with almost everything — its best to learn on the job, so start messing around in your local recording studios.

Almost every sampling plugin, sampling software or sample VST will allow you to adjust the attack, release and sustain of an audio section.

DAW’s in-built samplers often allow you to do a lot more, even Ableton’s ‘Simpler’, which might sound a bit misleading to start given how many parameter options there are! You can apply modulation such as LFOs, reptich and apply various filters and EQs, all of which have quite a dramatic effect on the sounds you're working with.

I’d highly recommend watching some tutorials online to get to grips with some of the theory before you get experimenting with it.

It would be foolish not to mention how much fun splicing up breakbeats can be.

From hip hop to UKG to DnB, this technique forms the basis of the drums for many dance music genres, so learning to quantize, crop, warp transients and layer breaks is a really useful technique to have in your Arsenal.

If you’re a DnB head, start with the infamous ‘Think Break’, which you should recognise pretty well.

Warping the sound by stretching it our or squishing it. Try doubling or halving the length of your sample….

This one is also great fun. As Four Tet revealed in his ‘In The Studio With Future Music’, one of his distinctive little tricks comes from using a short reversed section of audio to introduce the idea.

To finish, just a few words on something you should be aware of to avoid any potential legal trouble further down the line.

Clearance is the process of acquiring permission to use a sample, which is technically needed to prevent copyright infringement against the original rights holder. Not everything will require sample clearance.

The 'Amen Break' (the most sampled loop in history) for example is never cleared and is just widely accepted as public domain. But could The Orb get away with sampling Steve Reich’s Electric Counterpoint in Little Fluffy Clouds? Absolutely not.

Given its ubiquity, sampling is somewhat protected by the ‘Fair Use Law’, granting individuals ‘limited use of copyrighted material without permission from the rights holder’. If you’ve sampled a short sound, or have processed it into something unrecognisable you aren’t going to come up against any issues. Even if it is quite recognisable, in practice, unless there is some serious money to be made of your track and it's owned by a major label, the chances of anyone pressing charges against you are very slim. Unless the stakes are high, the legal fees alone would probably cost more than they are legally owed.

If you do find yourself in a position where something does need clearing however, it is definitely not something you can handle yourself. Obtain help from a label or publisher who really knows what they are doing. They will manage and clear it on your behalf and agree a royalty rate with the rights holder — percentage of the earnings from that track, potentially in addition to an upfront fee.